IWW: The Real Soapbox Heroes

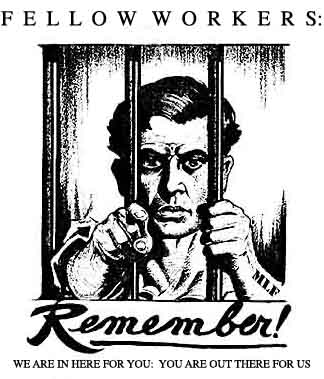

There are few living today who would associate the right to freedom of speech with the image of a scrappy hobo sitting in a jail cell. But in 1909, this very image defined what became known as the Spokane Free Speech fight.

The conflict began with lumber and agricultural workers resisting a profit-making scheme hatched between the employment agencies that referred jobs to workers and the companies that employed them. Designed to maintain a constant churning within the industry, the system kept “one crew coming, one working, and one going.” Workers often found themselves fired after only one day on the job, being forced to return back to the employment agency for another job at the cost of another dollar. This system of exploitation would have continued if it were not for the pugnacious group of agitators known as the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW or Wobblies). The IWW, founded in 1905, was a union like no other. Consisting of radicals, hobos and ne’er-do-wells, this union sought out the downtrodden, outcasts and those other unions considered unfit to be organized. Advocating industrial unionism rather than trade unionism, the Wobblies believed in uniting under “one big union.”

Since logging and agriculture workers lived in company-owned housing on company-owned land, organizing workers at the job site was risky and dangerous. To avoid this, the Wobblies did much of their organizing by way of public speaking and singing at locations where workers gathered to socialize.

Spokane, not so keen on the Wobblies, passed a law prohibiting street meetings and public rallies in an effort to deter organizing. The IWW honored the law for several months until the law was altered to favor the Salvation Army, which had a history of friction with the Wobblies. Both groups wished to save the working man; the Salvation Army wished to save him from damnation, while the other wished to save him from his boss.

Wobbly leadership saw this as not only a fight over free speech but also as a struggle for their union’s right to organize. The union put out a call throughout the whole organization for men and women to come to Spokane and test the city’s determination.

By November 2, 1909 hundreds of workers had flooded into Spokane, having come for the specific purpose of being arrested. One by one, they would stand up on a soapbox and promptly carried off to jail. In one incident, the police department took slightly longer to make the arrest. The man on the soapbox began his speech, “Felow Workers,” not expecting to continue, he was at a loss for words. Slightly embarrassed, he blurted out, “Where the hell are the cops?”

The first day, 103 speakers had been arrested. The Wobblies continued to flood into the city, up on to the soapbox and into the jail cells. Over the course of four months, 1,200 members had been arrested. When the Spokane jail filled, the city used every building available to house the new inmates, including an abandoned schoolhouse and a donated army barracks. The city figured it had spent over $250,000 to convict and jail the Wobblies, not counting the additional thousands of dollars weekly to house and feed the prisoners.

On March 4, 1910, the city released all of the free speech prisoners. The right of the union to freedom of speech and assembly was recognized by the city. More importantly, the employment agencies, whose insatiable greed sparked the incident, had their business licenses revoked and legislation was designed to regulate such businesses. Direct hiring of migratory workers by the businesses that employed them became the norm in Spokane thanks to the IWW.