Uppity Sinclair and the Battle of Liberty Hill

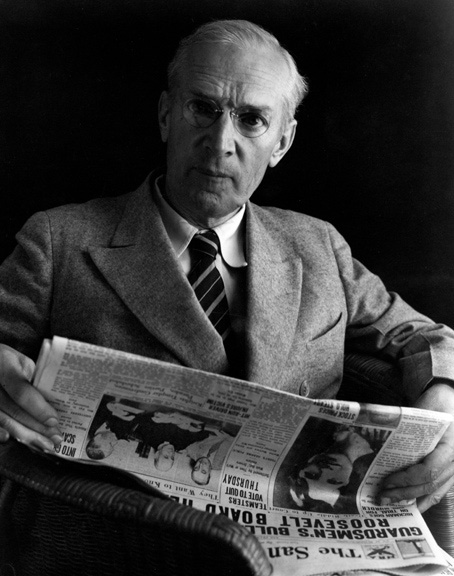

In the early evening of May 15, 1923, Upton Sinclair stood before a crowd on Liberty Hill in San Pedro. Known for years as a muckraker and radical author, Sinclair had a gift for using words to challenge social injustice. In 1906, he published The Jungle, a novel that told of the atrocious working conditions endured by Chicago Stockyard workers. Inspired by the ongoing battles in the meatpacking industry by the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen, the book caused controversy and ultimately led to the creation of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act.

But that evening in 1923, Sinclair chose to honor the hill’s namesake by using words to test the boundary between liberty and sedition. He spoke, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech . . .” Before Sinclair could finish reciting the First Amendment, he and three others were arrested. The arresting officer was recorded to have said, “We’ll have none of that Constitution stuff.”

As a lifelong labor advocate, Sinclair was not unfamiliar with being a champion of unpopular causes. His speech was in support of striking dockworkers with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), also known as the Wobblies. The strike was over low wages, bad working conditions, and the imprisonment of union activists under the Criminal Syndicalism Law – created specifically to criminalize the IWW.

During this time. Los Angeles proudly identified itself as an “open-stop” town, not friendly to union organizing. The police were used to ensure that unions did not gain a foothold in the city. They even employed the help of the Ku Klux Klan as strikebreakers. During the dockworker’s strike such tactics were utilized without hesitation.

However, Sinclair did not speak specifically about 3,000 striking dockworkers, nor about the 600 striking workers that had been arrested. Instead, he chose to illustrate that in L.A., a friend of labor is viewed as a dangerous threat, no matter what words are spoken. Sinclair proved to be correct. Shortly after the arrest, the Chief of Police commented that Sinclair was “more dangerous than 4,000 Wobblies.”

The publicity of Sinclair’s arrest was effectively more damaging then the speech itself. The arrests shifted a bright light onto Los Angeles, illuminating various seedy elements of the city; this unforeseen event led to the exposure of police corruption and the arrest of the Police Chief. All but 28 of the 600 dockworkers were released and the charges against Sinclair and friends were quietly dropped.

A week later, Sinclair returned to Liberty Hill and spoke to a crowd of 5,000 people, without incident. While labor strife continued over the next few years with the Klan and the police successfully being used as strikebreakers, the influence of Sinclair’s action and the determination of workers wanting to organize wanting to organize were stronger than the venom of anti-unionism. A foundation was laid for the explosion of the L.A. labor movement several years later that has continued even today. Also born out of this fight was the Southern California chapter of the ACLU to ensure that civil liberties are no longer threatened.

Today, overlooking the San Pedro waterfront stands a 9-foot-high bronze and stone pillar marking the site where Sinclair stood his ground. It not only symbolizes Upton Sinclair’s great act of defiance, but also the hollowed ground where Los Angeles became a union town.