The Pullman Strike and Battle for Los Angeles

On the night of June 27th, 1894, the American Railway Union sent out a telegram calling for a boycott of all Pullman sleeping cars. Early the next morning, a switchman at the La Grande Station in Los Angeles refused to attach two Pullman sleeping cars to a train departing for San Francisco. Similar incidents transpired throughout the country as other workers stood in solidarity with striking Pullman employees. Soon the U.S. found itself embroiled in a nationwide labor strife, impacting both its railway system and postal services. The Pullman Strike, as it came to be called, laid the foundation for a twenty-year long war between capital and labor in Los Angeles.

The prologue to the Pullman strike began with a serious economic crisis that hit the U.S. in the 1890s. In response, companies cut wages and reduced their workforce. George Pullman, the owner of the Pullman Palace Car Company, while priding himself as a benevolent employer, reacted as other employers did, with wage cuts and job reductions.

Frustration among Pullman workers rose when they discovered that the company stockholders still received handsome dividends. In addition and despite wage cuts, George Pullman refused to reduce the cost of rent and goods at the company-owned homes and stores. The striking workers organized with Eugene Debs’ American Railway Union (ARU) and sent a delegation to meet with employers over wage demands. The company responded by terminating the delegation, which led to 3000 workers walking off the job. The company then shut down the factory.

After several week of stagnation, the ARU called for a national boycott of all Pullman cars at its annual convention. Within four days, 125,000 workers on twenty-nine railroads had quit work rather than handle Pullman cars. Local 80 of Los Angeles enthusiastically supported the boycott and immediately refused to handle Pullman cars.

Within days, over three thousand union members in Los Angeles were on strike. Thousands gathered at the Hazard’s Pavilion to hear speeches and demonstrate their support. Other unions, including the printers, pressmen, carpenters, and retail clerks, provided financial aid. On the other side, Harrison Gray Otis, publisher of the Los Angeles Times, used his newspaper to attack the ARU and its members. The union responded by moving their picket lines over to the Los Angeles Times building.

Attorney General Richard Olney intervened on behalf of the railroads. He sat on the board of directors for several of the companies. Olney used the Sherman Anti-Trust Act to place an injunction against the ARU. He claimed they were interfering with interstate commerce and the delivery of mail. Authorities arrested ARU President Eugene Debs, the union’s board, and local leaders who disobeyed the injunction. Debs was sentenced to six months in Federal prison, while the rest of the board served three. In Los Angeles, a grand jury indicted six local ARU leaders, who were all sentenced to 18 months in prison.

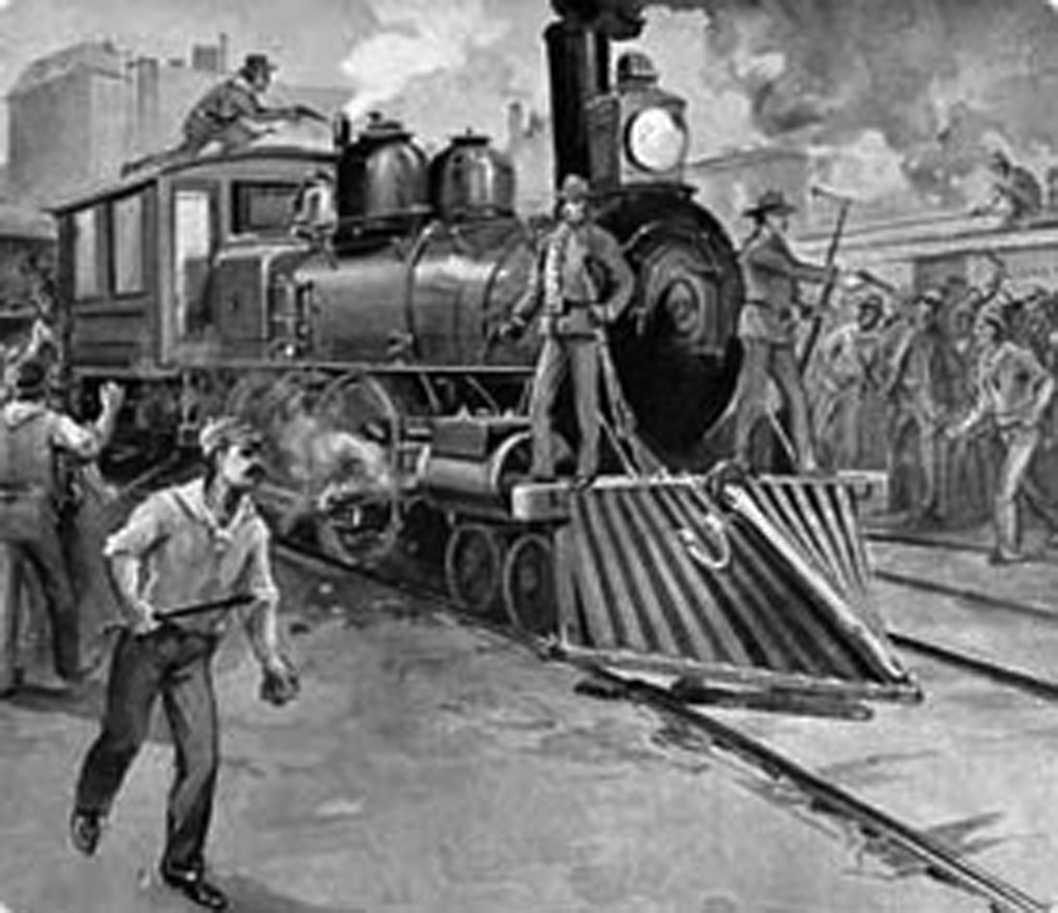

Throughout the country, the military was brought in to squash the strike. On July 4th, six companies of army regulars arrived in Los Angeles. Under the watchful eye of the U.S. military, trains began to move out of Los Angeles train stations the following day. The strike in Los Angeles was effectively subdued. Within a month, the ARU was forced to admit defeat.

While the strike lasted just a few weeks, it ignited a war in the City of Angels. Harrison Gray Otis, a man known for his hatred of unions, began to build the local Merchants Association into a powerful vehicle to keep unions out of Los Angeles. He soon found an ally with Henry E. Huntington, the nephew of the man who owned Southern Pacific Railroads. Together, they led the open-shop campaign and worked tirelessly to keep unions out of the city. For decades, the city streets were the battlegrounds between labor and capital; one-side armed with the finances of the elite and the other with picket signs.

The Pullman strike is acknowledged by many to be the birth of Los Angeles’s labor movement. And, though this movement had a tumultuous past, it survived the likes of Otis and Huntington. Today, at 16.6%, the union density of Los Angeles is 4.1% higher than the national average. And, while the city’s labor movement still has a lot of work to do, its current status is a far cry from what Otis’s Los Angeles Times had once hoped to report.