Look for the Union Label

For most who grew up in the 70s, the phrase “look for the union label” will cause an immediate reaction. Some will begin humming, while others will break out in song. Those old enough to remember will reflect back upon the commercial responsible for this musical reaction. Beginning in 1975, the International Ladies Garment Workers Union (ILGWU) began airing a commercial to promote products made by union workers and to encourage shoppers to look for the union label. While the commercial aired only 60 times in seven years, the song and its message reached 86% of the American public. Millions of Americans were now aware of the union label (a.k.a. the union bug) and why it was something worth searching for.

The history of the union label reaches back to the 1400’s; craft guilds often decorated their halls and seals with coats of arms containing visual symbols of the tools of their crafts. This continued until the advancement of printing technology in the 1800’s, which expanded other avenues of promotion for craft unions (i.e., membership cards, buttons, badges, etc.) As the labor movement began to take hold in 19th century America, trade unions would continue to use the tools of their craft on their logos combined with the name and local of their union. At this point though, there was no signifying mark to indicate a product was union-made.

In the 1860’s, 8-hour leagues developed throughout the United States in an attempt to reduce a day’s work from ten to eight hours a day. In 1869, one of these groups, the Carpenter’s Eight-Hour League in San Francisco, adopted a stamp to be placed on products produced in mills and factories whose employees worked eight-hour shifts. This stamp is considered to be the precursor to the union label.

During the same period, a less admirable side of the labor movement was also forming on the west coast. With the rise of Chinese immigration and their exploitation as cheap labor by employers, a wave of racially motivated hysteria swept through the West. In the midst of economic depression, Chinese workers were imagined as complicit partners of big business, their cheap labor driving organized, white laborers out of work. This hysteria led to numerous race riots and eventually to the Chinese Exclusion and Geary acts.

While most craft unions were never directly threatened by Chinese labor, small-producer guilds (shoemakers, boot makers, cigar makers) were finding their handcrafts displaced in the market by cheaper goods that were mass-produced by Chinese labor in San Francisco. As a response, in 1874, the cigar makers in San Francisco created a “white labor” label to indicate that unionized white men rather than non-union Chinese workers made the product. The Shoemakers’ Protective Union also followed suit, adopting their own “white labor” label.

The Cigar Makers International recognized the potential support that working class consumers could provide in encouraging the production and sale of union products. They initiated the first national union label in 1880, this one blue in color, thus doing away with the racially motivated white label from the West. Other unions rapidly followed suit in the next decade, including those representing typographers, garment workers, coopers, bakers and iron molders.

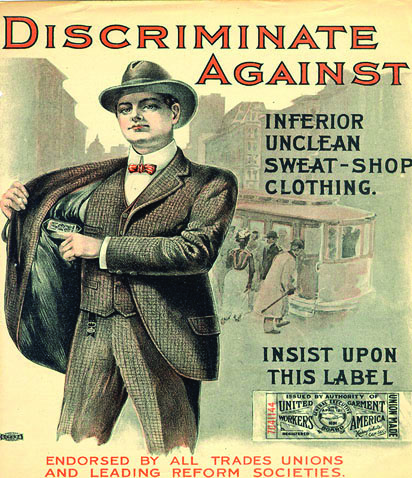

By 1909, the American Federation of Labor formed the Union Label Department to spread the use of the union label. As William Green, President of the AFL in 1939, noted, the label’s presence on a product is representative “of those conditions surrounding working men and women which make for a higher and better standard of living.”

Today, the union label represents a broad, multi-ethnic labor force. While we know it as a symbol for products made by union workers, it is also symbolic of labor’s past. Even in its birth, with the struggle for the 8-hour day and the “white-labor” label, the union label represents the movement’s mixed history of pride and shame. But, within that history, there also exists many great labor leaders, like A. Philip Randolph, Addie Wyatt, Dolores Huerta, and Rose Pesotta, who fought against racial intolerance and gender discrimination. Despite its shortcomings, labor has continued to be at the forefront of progress for all workers, regardless of race, gender, or creed. It is also because of this that we should continue to look for the union label.