Frank Little: A Murder in Butte

In the early hours of a hot August morning in 1917, the body of a young union organizer hanged off a railroad trestle near Butte, Montana. The body, beaten and bloody, was that of Frank Little, a member of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). Pinned to the body was a note that cautioned, “Others take Notice! First and Last Warning! 3-7-77 L-D-C-S-S-W-T.” The numbers were said to represent the measurements of a grave; the letters represented the initials of several union organizers. The “L”, which represented Little, was circled. The message was clear: union organizers leave town or succumb to the same fate.

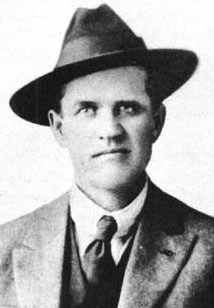

In his earlier years, Frank Little had worked in the mines and had been active in the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). When the WFM and the IWW split ways, Little stayed with the IWW, traveling throughout the western states to where ever workers were waging a battle with their employers. It was this determination to be in the middle of the fight that led him to Butte, Montana.

Butte had been a battleground for unionism for nearly four decades prior to Little rolling into town. In 1917, the high number of deaths and injuries in the mines began building tension in the city. This stress was exacerbated by the low wages paid to workers and the increased production due to the U.S. entry into World War I.

On June 8, 1917 the powder keg exploded when a fire rushed through the Spectacular Mine, killing 168 miners. The fire triggered a walkout by the mine workers, who swiftly formed a new union, Metal Mine Workers’ Union (MMWU). Other trades joined in the strike, but on behest of a federal mediator were convinced to go back to work. The employers then proceeded to establish a “home guard” to patrol the streets and assault the striking workers. Local newspapers, owned by the mining company, were used to undermine public support for the striking workers.

Frank Little arrived in town on July 18 and immediately set out to aid the striking mine workers in the struggle. He urged the use of picket lines, not yet implemented around the mines. Women, with Little’s encouragement, formed a committee where they too joined the pickets. The other unions, who had previously gone back to work, heeded his criticisms and walked off their jobs once again. Within two weeks of his arrival, Little’s experience in labor strife had successfully turned around the strike for the miners.

The Anaconda Copper Mining Company and law enforcement took notice of Frank Little’s presence. They opened investigations to see if his speeches could be used to prosecute him for sedition, but the investigation came up empty. Since Little could not be dealt with through legal means, some parties decided to take matters into their own hands.

In the early morning of August 1, six men arrived at the boarding house where Frank Little stayed. The men entered the house identifying themselves as officers, gagged a struggling Little and carried him to the awaiting vehicle. It has been reported that after traveling a short distance, the car stopped and Little was tied to the bumper where he was then dragged several blocks. Upon arriving at their destination, just outside the county line, the men carried the young organizer to the side of the bridge where they proceeded to throw him off. His hanging body was discovered early the next morning.

The news of Little’s death spread far and wide. IWW members, militants and unionists flooded into Butte to pay respect to their fallen brother. Ten thousand people crammed the streets of the town to watch the funeral procession that included an additional three thousand five hundred friends and supporters.

The six men who killed Frank Little were never arrested for his death. However, those on both sides of the conflict, including law enforcement, knew their names. Some of those believed to be involved had actually been members of the police force; others were company detectives and hired guns. Today, the patch worn by members of the Montana Highway Patrol has the numbers “3-7-77”, the same numbers written on the note pinned to Frank Little at the time of his death. The numbers were added to the patch in 1956 to revere the history of vigilantism in the state.