The Elaine Massacre: An American Tragedy

On Sept. 30, 1919, a group of nearly 100 black sharecroppers was holding a union meeting in a small church in Hoop Spur, a tiny hamlet near Elaine, Arkansas. The group, members of the Progressive Household Union of America, was determined to secure a fair settlement from the planters for the yearly cotton crop. The events that followed are disputed; however, what is known is that within a few short minutes, a shootout ensued between participants of the meeting and deputies. One officer, W.H. Adkins, was killed, while another was critically injured. What followed was one of the largest and most vicious race riots in American history, leaving hundreds of people maimed, beaten and murdered. The event would become known as the Elaine Massacre.

Shortly after the First World War, many black servicemen returned home determined to exercise their rights and demand greater freedoms. Despite this resolve, they returned only to find a nation still segregated by race, a Red Scare and labor strife. Many found little opportunity for employment beyond low wage, back breaking work, such as sharecropping. Attempts made in the past to organize sharecroppers often led to violent confrontations, since it was often viewed as a direct challenge to the system of Jim Crow servitude in southern plantations.

Local planters became alarmed when they heard of the union and began circulating rumors that the union intended to murder whites and take their land. After the shooting, this rumor was woven into the report that would become the official storyline. Newspapers reported that two deputies and a black trustee were traveling together when their vehicle broke down outside of a meeting of sharecroppers who were plotting to kill white planters and take their land. Two sentries outside of the meeting shot at them and they returned fire. The sharecroppers contended that whites fired into the church to disrupt the meeting and that blacks returned fire only in self-defense.

The story of the incident spread throughout the region and when a posse was dispatched to arrest those involved, armed whites throughout the neighboring counties and states soon arrived to join in the growing mob. It is estimated that the mob grew anywhere from 600 to 1000 in number.

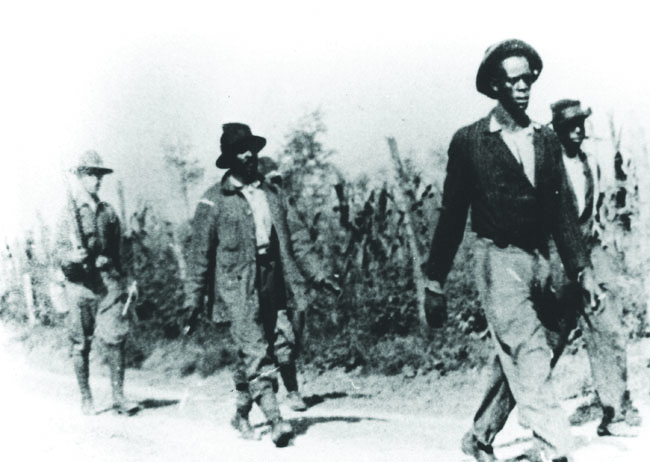

The white population went on a rampage against the black citizens, most of whom played no part in the union organizing. Men, women and children were attacked, beaten, killed and lynched. Ears and toes of dead African-Americans were severed for souvenirs, while their bodies were dragged through the streets. For three days, blacks lived in fear of their white counterparts, staying hidden in the nearby sugarcane groves, except for those with military service who defended themselves against the roving mobs.

On Oct. 2, the Governor brought in federal troops to disarm those involved and restore order. However, rather than squashing the massacre, some of the troops actually participated in the mass slaughter of unarmed blacks. Other troops did assist many blacks in fleeing from the violence.

At the end, the estimated death toll among blacks ranged from the official total of 26 to several reports of roughly 856. In fact, it is likely that as many as 200 African-Americans lost their lives. Five whites were killed. In addition, 285 black men were arrested, along with only one white person (the union attorney’s son.)

Days later, city officials issued a report stating that no riot or mob violence occurred. In fact, the report stated an insurrection (of blacks) was put down within the boundaries of the law. Less than a month later, a grand jury indicted 122 African-Americans with second-degree murder and night riding (a law often used against the Ku Klux Klan.) The only white man threatened with possible prosecution was the union attorney’s son, who was also working for the union. In total 65 of those arrested were sentenced, with 12 of them sentenced to death. Later it was reported that many of those arrested were tortured into confessing various crimes. It took six years and a series of retrials and appeals before those convicted to die were finally released.

To this day, the complete story surrounding the events known as the Elaine Massacre is still unclear. But as blurred as the facts may be, it is transparent that much of the conflict was guided by racial intolerance. It was fueled by the fear that those who are viewed as “inferior” might demand to be counted and respected for the work they do. While some may view this incident as a page in the chapter of the black experience, it is just as much a collective history for all Americans – a history, albeit tragic, that we all need to recognize.